You know it’s a Disney/Pixar production when we get a dead parent in the story.

This time they upped the ante and gave us a dead protagonist! Well, undead protagonist?

Soul ambitiously explores life, death and purpose in a way a Pixar animation wouldn’t be expected to. As such, I felt this film’s target audience was older, maybe even adult as it deals with existentialism and nihilism in a way that would be difficult for children to connect with. Think Pixar’s Inside Out, but better.

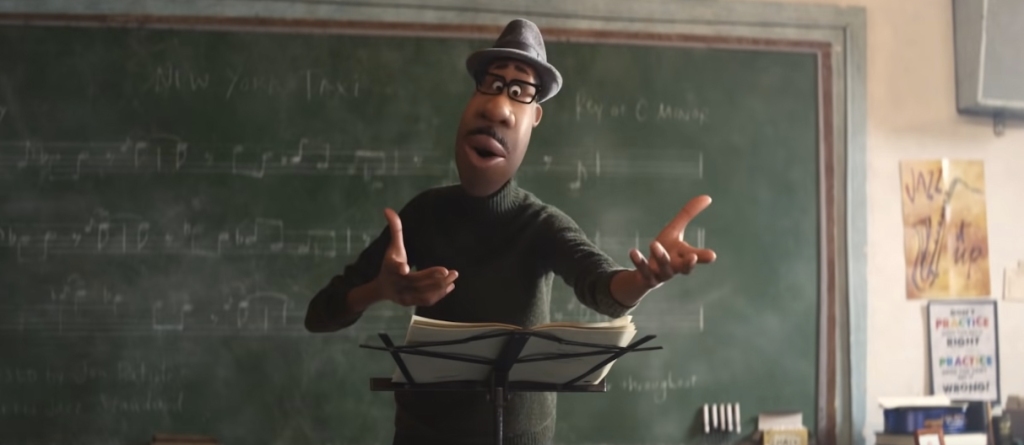

Joe Gardener, a school band teacher who dreams of pursuing his passion of jazz music as a full-time career, meets unborn soul ‘22’ in The Great Before after tragically and comically falling down a manhole on Earth. The concept that drives the story is the comparison of a soul that doesn’t want to live (22) against a soul that doesn’t want to die (Joe).

The story is clever and thoughtful and presents ideas of purpose and reasons for living that may challenge conventional notions. The use of 22 as a learning device for Joe also helped the audience to consider the same questions of purpose and finding one’s ‘spark’ as Joe and 22 learned from one another. 22’s innocence and naivety of life on Earth allowed Joe to appreciate that which he had taken for granted. Similarly experiencing Joe’s life allowed 22, a non-living entity, to utilize all five senses and appreciate being alive, in a way mentoring could not help before. They say experience is the best teacher after all…

I really enjoyed the intentionality behind the characters, specifically 22. In numerology the number 22 represents balance, perfectionism and idealism. Through the character of 22, idealism is portrayed as practically impossible. Where the number 22 represents perfect balance, without swaying to one side or the other, it follows that the character 22 cannot find their spark when they are perpetually on the (spiritual) fence. The film comments on our limited and rigid perceptions of purpose and how sometimes we can get caught up chasing our idea of perfectionism and forget the value in just living and being present. This is brilliantly exemplified in 22’s exchange with Joe’s barber, Dez. Joe discovers a whole other dimension to Dez simply through 22’s inquisitive nature, exposing how myopic and inadvertently self-centered Joe’s mentality had previously been.

When Joe won’t accept that his suit doesn’t fit anymore this again represented limited and rigid perceptions of purpose. The suit ripping had the same effect as him falling down the manhole; it forced him to stop and look at the bigger picture, to consider alternative perspectives.

The creative world built in this film really allows you to buy into the ‘rules’ of that universe. The Great Before, The Great Beyond, and The Zone, specifically, are all fantastically crafted and described in a way that aligns with our human experiences.

I loved the meaning given to one’s ‘spark’, in that instead of representing life’s purpose, it simply means that a soul is ready to live. To want to live and experience life is rarely valued in terms of purpose and the film does really well to inspire this conversation. When 22 goes from feeling everything, to feeling nothing and thus becomes a lost soul, it adds weight to the meaning and perhaps another layer of understanding for those who have felt like lost souls before.

I particularly enjoyed the juxtaposition of the character Moonwind’s living body and his soul. Eccentric and seemingly nonconformist in the real world, but perfectly lucid and coherent in the lost soul world. It nods to the notion that people who have reached a certain level of enlightenment are able to transcend physical and spiritual realms, and live unconcerned about the perceptions of others. This follows on with the theme of open-mindedness and considering other perspectives and I thought it was a thoughtful but comedic way to demonstrate the separation of body and mind.

This Pixar production took detailed animation to new heights and does not disappoint. The intricacies of kinky afro hair are so impressively depicted that you can practically feel the textures through your eyes. It was a nice touch of authenticity to have a ‘soul-searching’ conversation (pardon the pun) in the barbershop, a location known to be a communal hub in Black communities. From the scene in the barbershop to the pictures on the jazz club walls, to the way light reflects off of different Black skin-tones, it was heart-warming to see appreciation for the nuances a Black protagonist requires.

Although a largely enjoyable watch, it did occur to me that animated features with a Black main character always end up morphing the character into some other thing. This is seen in Disney’s The Princess and The Frog, where Tiana is a frog for the majority of the film, as well as in Spies in Disguise, starring Will Smith whose character transforms into a pigeon. When Joe’s soul went into the cat in Soul I rolled my eyes, and while I understand it served the plot for Joe to observe himself outside of his own body, sometimes let’s allow Black people to be people for the whole film.

One thing that I couldn’t quite understand is why Joe never became a lost soul. Surely, he fulfilled all the requirements, with his one-track state of mind thinking about his career as a jazz musician. According to the rules of the film, he should’ve been a lost soul at some point.

That aside this film is a fitting remedy for the year we have had, in a time where we all have more space for self-reflection. In the middle of this panini, I think the most important moral to take from Soul is to not lose yourself trying to find your purpose and to try to find joy in the smaller things.